|

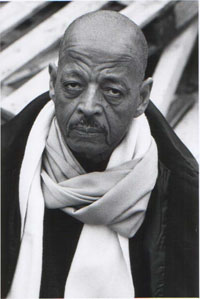

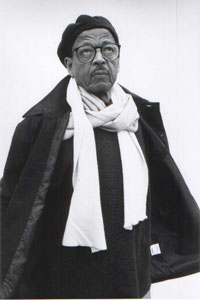

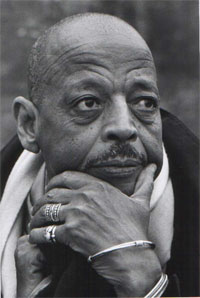

There is a definitive analogy between my work as a painter and my work as a filmmaker, which I am a painter. Each work of art is different. I paint essentially for myself. I see myself essentially as a painter, but I also come to life as a filmmaker. Hussein Shariffe was born on July 7th, 1934 in Omdurman, Sudan. His father Dr Mamoun Hussein Shariffe was a medical doctor and grandson of alKhalifa Shariffe and his mother was Sayda Shama Abdelrahman AlMahdi, daughter of Al-Imam Abdelrahman ElMahdi. His parents were first cousins and his great grandfather was Al-Imam Muhammed Ahmed El-Mahdi, Sudanese politician and religious leader, the single most influential personality in the history of the modern Sudan. Childhood Years He spent his childhood in Wadnabawy where his parents lived and at an early age attended the Kuttab and Khalwa with his cousins where they were taught reading and reciting of the Quran. The childhood years were filled with little artistic games playing with mud, drawing pictures and making theatrical plays, which he wrote and he and his cousins acted. Shariffe’s primary education began in Ahfad school for boys and then in Comboni school. In Comboni he was introduced to art as a study, where his art teacher encouraged him in further developing his talents having sensed his artistic gifts, as such he taught Shariffe drawing on posters and watercolours. Victoria College

In Victoria College, Shariffe with his fellow colleagues were introduced and taught music, art and poetry, in addition to languages and theatre. It was here that Shariffe made his first serious attempt in painting. Slade School of Fine Arts After Victoria College, Shariffe went to England where he studied Modern History at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge. "The Cambridge years were uneventful but pleasant. I made lasting friendships and still value the friendship of journalists like Nicholas Harman and Richard Kershaw, both of whom I first met in Cambridge. And there was Jonathan Miller, the famous theatre and opera director and producer, there were 10 Sudanese at Cambridge at the time, including my late cousin Al-Taher El-Fadel and Ambassador Mustafa Medani.." Interview with Gamal Mkrumah, AlAhram newspaper, August 2003. His choice of studying History was a compromise for his family's wish for him to study either medicine or law and his wish to study art (to which his father and uncle El-Imam ElSiddig opposed to). Despite the wish to compromise, Shariffe was not satisfied with what he was studying and made an academic shift to studying Architecture in Sheffield University, hoping that in studying architecture he might be closer to his wish. Alas, that was not so and the ‘painter to be’ followed the advice of some of his friends and applied to Slade School of Fine Art. The application deadline had already closed and it was the end of the academic year, but despite this Shariffe received acceptance to join Slade. In fact, one of the lecturers in Slade also paid a visit to Shariffe’s father to convince him that his son was talented and to allow him to study art.

Al-Sayed Abdel-Rahman Al-Mahdi, was very supportive of his grandson's endeavours "My son, I know that this is not a conventional or profitable trade. But if you love it go ahead. God bless you," his grandfather told him during a farewell visit before Shariffe's departure for England. His grandfather kissed him on the forehead. That was the last time he ever saw his grandfather. Interview with Gamal Nkrumah, AlAhram Weekly, August 2003. In UK, he was awarded the John Moores prize for young artists & in 1958 he made his first solo exhibition in Gallery One, London, this was followed by a second solo exhibition in 1960, again in Gallery One. Painting and the Cinema In 1960, Hussein Shariffe chose to settle in his homeland returned to Sudan. In 1961 he married his first cousin Shama ElMahdi (daughter of El Imam ElSiddig), in a traditional Sudanese wedding. Shariffe began working as a lecturer in the Faculty of Art, School of Fine Arts, Khartoum. After 4 years working as a lecturer he realised that his real place was not in teaching art, and that if he continued he would be unfair both to his students and to himself. To Shariffe, the 60s & 70s were a time of intense exploration and socialization. His home was a comfortable venue to colleagues, and to those interested in the arts to meet and hold discussions on subjects of interest, and in it he and his wife Shama were hosts to people who remain friends to this day. Shariffe exhibited a passion that was enchanting and his home was always beautifully welcoming and filled with a somewhat ‘modern Sudanese hospitality’. It was at this period that Hussein Shariffe founded Twenty One a literally arts periodical. Twenty One was an attempt to bring Africa into the focus, where articles from African writers were published, unfortunately only 4 editions were sent to print. This was a period where he exhibited his works in more than 8 different exhibitions and galleries, in different countries. He was described by critics as one showing great talents of a unique kind, his work was expressed as having innocence that is close to the heart (these quotes were respectively from The Guardian and the Spectator).

"Cinema has the ability to communicate across cultures and social classes. Illiterate people can relate to cinema. You don't have to be highly educated or cultured to connect to cinema." Alahram Weekly 2003, interview with Gamal Nkrumah. To him reaching out to people was essential for an artist, it was important to him that he present to his country something of depth and meaning, a way of bringing to his audience some of what he felt, about his country and the people of his country.. In the early 70s Shariffe was introduced to his first trial in filmography. This was through his late friend and colleague Ali ElMek, who was working with him in the State Corporation of Cinema. Ali ElMek introduced Shariffe to the French writer and film director Henri Herve, who was visiting to Sudan. Herve was working on a documentary film entitled ‘Facts’, about the life of Hans Steiner, a German mercenary captured in South Sudan. The film discussed the issue of mercenaries and their role on the continent. Both Hussein Shariffe and Ali ElMek were interested in working with Herve and indeed they immediately set to work in their first film project. As Head of the Department of State Cinema, Shariffe's role was to write about the Sudan, and the two friends worked energetically in producing the film, they filmed the court proceedings of Steiner and even had an interview with him. This was a joint venture between the Sudanese State Cinema and the French Film company, its success would be the start of a new venture for Sudanese cinema, as such Sharifffe and ElMek were very excited about the project. At the end stages of production of the film, Shariffe went to Paris to see a review of the final cut of the film prior to montage, when he received a telegraph that they should stop the filming and end the project. Apparently a lot of politics was involved in the issue, leading to the release of Steiner from prison. Shariffe was frustrated with the death of the project and the silencing of the truth, he decided he would not return to Sudan. At the same time his friend and colleague Ali ElMek was facing a lot of discomfort in the department and in 1971 he was sacked from the job. In response Shariffe submitted his official resignation from the State Cinema. Shariffe returned to Sudan and in 1972 flew to London where he met his friend and colleague Ibrahim Salahi. Salahi had been invited to work on a new department in the Ministry of Culture and Information. He requested that Shariffe join him in this new venture, It was another governmental position, but it was new and it required a lot of work. Shariffe accepted and returned back to Sudan to become the Head of Film Section in the Department of It was during this period in the Department of Culture that Shariffe directed his first film The Throwing of Fire, in 1973. It was also the first film to be produced by the department. After this first attempt and during the coming period, the political climate became much harder to tolerate, there was a lot of instability and a lot of hardships. Shariffe himself was sick for a long period and during this tough and emotional time, the idea of the film on Suakin began to evolve. Determined to further acquaint himself about the cinema, Shariffe applied to the National Film School in UK. He was accepted (from 1000 applications only 25 were given a position) and left to study Film writing and directing. Studying filmography was an eye opener to Shariffe, the school was a governmental institution, that was well funded and provided good quality in both the teaching and the equipment provided for the students. Suakin was filmed in 1974, and the final edit for it in London was in 1975, ęShariffe wrote the screenplay, directed the film and designed the ęcostumes for the film. He named it Dislocation of Amber. In 1976, Shariffe’s family (his wife and four children) went to UK to settle with him. It was a period where he worked enthusiastically finding his new self in the World of Cinema and at the same time painting and exhibiting his works in different galleries and exhibitions. In 1979, Shariffe made his second complete film, Tigers are Better Looking, an adaptation from a story by Jean Rhys. In 1985, Shariffe made a documentary for UNICEF, Sudan called Not the Waters of the Moon, it was an e In Sudan, Shariffe began working on a project to document the life and works of AbdelAziz Dawood, at that time, Dawood was alive and he himself had requested that the film be directed by Shariffe. On his return from filming in Juba, Hussein Shariffe was greeted with the devastating news of the death of AbdelAziz Dawood, hence the project of the documentary was brought to an end. After a period in UK, In August 1987, Shariffe returned to Sudan, already his family had gone ahead of him. It was a time of democracy in the Country, but still there was little political stability. Shariffe soon came with the idea of a documentary about the life of AlWathiq Sabah Alkheir (AlWathiq was described as the Robinhood of Sudan, who robbed from the rich to give to the poor). Indeed they began filming the film, but in 1989, the political instability in the Sudan reached its maximum and a military coup occurred in the country ridding the Sudan again of democratic rule. Shariffe went to Cairo, which at least had similarities to his homeland, both in geographical and cultural sense, in a hope to reduce his feeling of exile. In Cairo he continued his work as a painter and made new and again long lasting friendships with the Sudanese, Egyptians and Westerners living or visiting the land of the Pharoahs. Egypt was much open and acknowledged art work and artists, the environment was a lot more conducive in comparison to Sudan. In 1993, Shariffe with the Egyptian Film director, Attiyat AlAbanodi, made a film Diary in Exile, a documentary on exile, which was premiered at the United Nations Human Rights conference in 1993, in Vienna. In 1997, worried by the fact that so many Sudanese intellectuals, writers, artists and singers were forced to leave their country due to the lack of freedom of expression to live in exile (including himself and a lot of his friends), Shariffe began the idea of his last cinematic work Letters from Abroad. To Shariffe Letters from Abroad was his unique way of giving to his Country, it was about exile, it was about identity, the identity of Sudanese in different countries. On the 21st January 2005, Shariffe passed silently away, leaving behind him his incomplete film, a film which he would have starved himself to complete…. The True Colours of Hussein Shariffe Most of us have experienced the warm welcome of Hussein Shariffe: smiles and a genuine interest in the person he meets. He liked conversation and was modest and humble about his breath of knowledge. Hussein was generous in spirit and in kind. He was loyal to his friends and loved by all. He always found some good words to say about people. Truly there was no malice in him. He was a man of etiquette and courtesy and he always had a concern for his friends. Ahmed Al-Shahi, speech delivered at the gathering of the ‘celebration of the life and works of Hussein Shariffe, London 10th July 2005, University of East London. Hussein Shariffe was a refined, sophisticated person, he was a sensitive, charming As a husband, Shariffe cared immensely for his wife, Shama, she was his wife, sister and closest friend. As a couple they were sociable, who always had friends and family with them. During their early married life in Sudan their house was a haven where artists and intellectuals met and socialised. Shama dedicated her life with Shariffe, standing close by his side during the most difficult and the best of times. For her loyal support she earned Shariffe’s respect and appreciation, she was his pillar. In the 60’s and 70’s Nasra, Mamoun, Aisha and Eiman were born. Bringing up the children and the responsibility of the house including its financial aspects were all undertaken by Shama, which gave Shariffe the space and energy to work on his art. As a father, Shariffe adored his children and was proud of them. Although he was not always with them especially during their childhood years, he still developed a special relationship with each and every one of them. Strangely enough, despite his strong passion to his work, Shariffe never talked about it at home. Perhaps, he wanted everyone to choose their own career and have their own choice without his influence? Shariffe treasured the lifelong friendships which he had built during his life. His friends were the most closest to him, they understood him and had profound respect for him. He loved their company, enjoyed cooking for and entertaining them. To the youngest of his friends he became their mentor, guiding them and supporting them in each and everyway. As such on his death, he was mourned by many, whom remained loyal to his endearing friendship. |

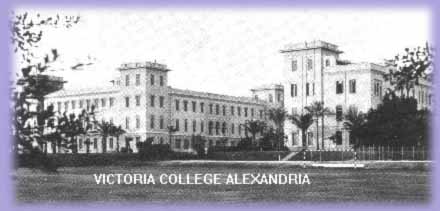

Following Comboni, Shariffe with his fellow cousins were sent to Victoria College (Victoria College, Alexandria, was founded in October 1902, and was named after the British Queen Victoria. Deliberately fashioned as an independent, secular school, Victoria college was open to anyone who could afford its fees, attracting the children both of the elite–royalty, diplomats, magnates, politicians, landowners–and of very ordinary people. Its pupils came not only from all over Egypt, but from the entire Middle East and beyond.).

Following Comboni, Shariffe with his fellow cousins were sent to Victoria College (Victoria College, Alexandria, was founded in October 1902, and was named after the British Queen Victoria. Deliberately fashioned as an independent, secular school, Victoria college was open to anyone who could afford its fees, attracting the children both of the elite–royalty, diplomats, magnates, politicians, landowners–and of very ordinary people. Its pupils came not only from all over Egypt, but from the entire Middle East and beyond.).

Shariffe truly excelled in his art profession, but alas he still felt troubled that he had not realised all his dreams. His true desire was to reach out to everyone with his work, but it was clear that through his paintings those whom truly appreciated it were really Sudanese elitists, intellectuals or Westerners. His wish was to communicate with a much larger audience and for him the only way to do that was through the cinema.

Shariffe truly excelled in his art profession, but alas he still felt troubled that he had not realised all his dreams. His true desire was to reach out to everyone with his work, but it was clear that through his paintings those whom truly appreciated it were really Sudanese elitists, intellectuals or Westerners. His wish was to communicate with a much larger audience and for him the only way to do that was through the cinema. Culture in the Ministry.

Culture in the Ministry.  ducational film to encourage vaccination of children.

ducational film to encourage vaccination of children.  character who dressed elegantly, spoke eloquently and had a good sense of humour. His style was unique and with his small build, he looked much younger than his age. He spoke fluently in Arabic and English languages and also knew French. He loved beauty and wherever he stayed he turned the place into a piece of art.

character who dressed elegantly, spoke eloquently and had a good sense of humour. His style was unique and with his small build, he looked much younger than his age. He spoke fluently in Arabic and English languages and also knew French. He loved beauty and wherever he stayed he turned the place into a piece of art.